Renee Erickson's Accidental Empire

Image: Jonny Ruzzo

Renee Erickson awoke to a flurry of Instagram tags from her various restaurants’ accounts. One dish from her newest spot, Lioness, made her squint especially hard. What was that—oatmeal?

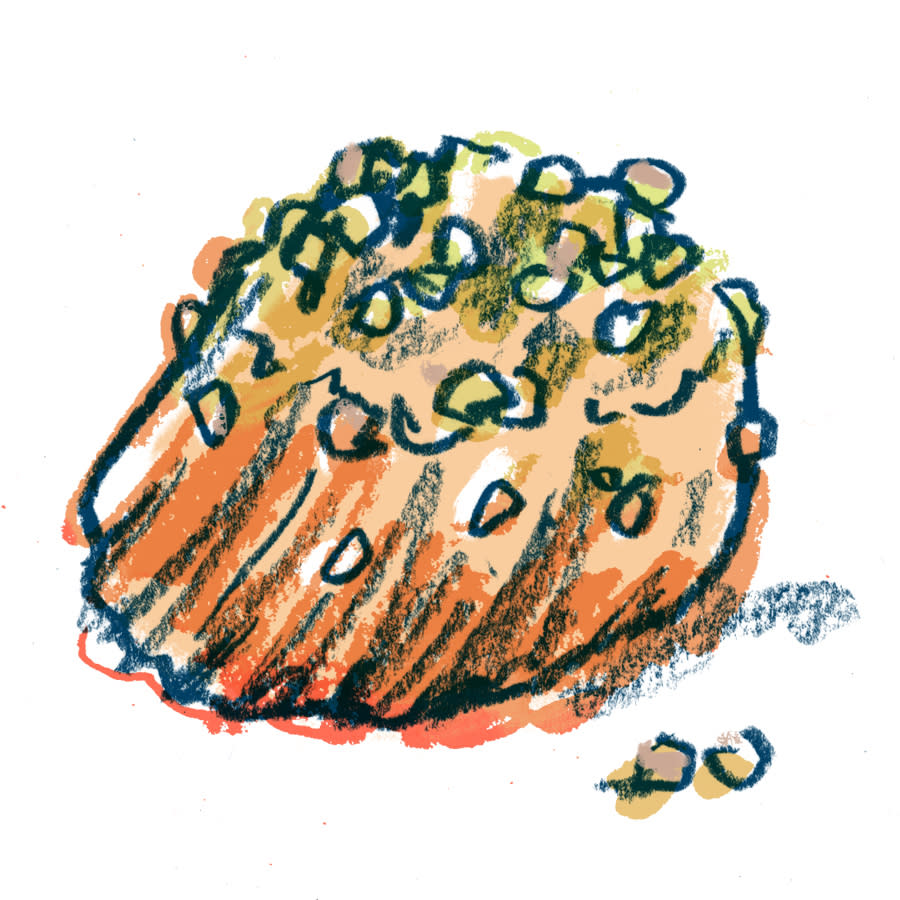

Nope, it was scallops topped with nuts. Erickson sent a screen shot to Bobby Palmquist, the executive chef for her Sea Creatures restaurant group. She wanted to know, “Why are we putting nuts on something that’s so delicate?” Later that day, Palmquist teased his boss about her early morning query: “I have the best job in the company.” She's not uncomfortable giving feedback, though if you're trying to fact check, say, a story about her restaurant group, Erickson will maintain that every good idea, every successful dish comes directly from the chefs de cuisine.

And at Lioness, there are plenty of those dishes. The loud and lively Italian bar opened in January with all of eight indoor tables, each one full from the minute the doors open every day. Inside, candles flicker in Chianti bottles; Erickson picked out the custom-painted plates that hold oysters, smoked cod mousse, and a meatball so compelling it needs no spaghetti.

By 5:30pm one recent Saturday, the waitlist was already so long, Lioness was theoretically full for the rest of the night. General manager James Ingles had to break the news to arrivals hoping for a table. The bar area is too tight for seats; customers must stand, as drinkers do in cities like Rome or Barcelona. It’s a very un-American concept, but occupants seem too busy with their martinis—served on a tray with a choose-your-own garnish setup—or glasses of Montepulciano to mind.

Image: Amber Fouts

Lioness already operates with the assurance of a place that’s been in motion for a year. In part because the trio that created it have been in motion together for nearly 15.

Erickson and her business partners, Jeremy Price and Chad Dale, came together to open Walrus and the Carpenter in 2010. Their first project captured lightning in a rosé bottle, not to mention the cover of the New York Times travel section.

Their latest venture feels like a full circle moment: Another elbow-to-elbow bar with great food, hidden from the street but joining other nearby businesses to create a sense of place. Both spots have menus that vault far beyond typical bar food, plus a distinct style that takes cues from Europe. They are tiny spaces with big chandeliers and an even bigger footprint on Seattle’s dining psyche. But a lot has happened between Walrus and Lioness.

“Renee never set out or wanted to be a restaurateur, right?” says Dale. “She always wanted to have that one restaurant and be there cooking every day.” Dale is a developer; we’re having this conversation atop the Shared Roof building, his latest project. Five floors below us, Lioness is hidden away in a courtyard. “That part of our partnership has been a blessing,” he says. “They hold me back, and I push them a little bit.”

Most new Sea Creatures projects originate with Dale. Price is a bridge—a guy who knows what it means to bus tables or manage a frantically crowded dining room, but also relishes design and can wrap his brain around the nuances of health insurance plans. A fourth partner, Ira Gerlich, came on in 2018 and is mostly silent.

Image: Amber Fouts

It’s not an accident the company isn’t called the Renee Erickson Restaurant Group. But we inevitably refer to any Sea Creatures project as a Renee Erickson restaurant. “It was always pretty clear that if we were a band, she was the front person,” says Price. “Chad and I are playing bass or on the drums or something.”

As lead singers go, Erickson’s a compelling one—a chef who spends her off-hours crabbing on Puget Sound with her parents and husband, or exploring Normandy or Rome or Baja for inspiration. Restaurant life lured her away from studying fine art; Erickson once brought a beloved dog to the paint store to color match a certain spot in his fur because she wanted the walls of her first restaurant, Boat Street Cafe, to be that same shade of luminous white.

Everything about her says small, direct, personal. That might be why the scale of Sea Creatures hides in plain sight. Together, these bespoke little restaurants add up to one of the most influential, and quietly prolific giants of Seattle’s restaurant landscape. The company currently runs 10 venues (14 if you count each General Porpoise doughnut shop individually) with three more on the way. Sea Creatures employs 250 people, depending on the time of year, most with health insurance, retirement savings, and wellness benefits. They put out food that captures national attention and James Beard Award acclaim. The cross-purposes baked in from the start—a chef ambivalent about empires, a developer eager to build one—might be the proprietary blend that makes this all possible.

“Chad knows how to build quality projects,” says Tracy Cornell, one of the city’s go-to brokers who helps put restaurants in commercial spaces (she worked with Sea Creatures on its projects on Capitol Hill years ago). With Shared Roof, “he built the nicest project on Phinney Ridge.”

People who have worked with Dale say he’s a savvy, even tough dealmaker. Sea Creatures benefits from having him in the mix, but the benefit runs both ways. When Renee Erickson is involved, says Cornell, “Everyone’s rolling out the red carpet. Any one of my listings, I could have gotten my landlord to deliver her a turnkey deal; no question about it.”

Erickson fell into cooking with zero long-term idea of what her career would look like. The food drives her, whether it’s fine tuning her chefs’ dishes, or the four-page company guide that details the local, sustainable pathways Sea Creatures restaurants should use to source produce and proteins. (“If you want to serve trout it has to be fed non-GMO feed and in a closed-loop system.”)

Image: Courtesy Eric Tra/Lioness

For her, a new endeavor “has to feel—at least as much as it can feel—as something I’m really excited about. That’s why the merging with Great State and all that was just fucking terrible.”

She’s talking about her company’s acquisition of chef Josh Henderson’s restaurants, also known as one of the weirdest surprises in Seattle restaurant history. Sea Creatures’ partners are candid about the missteps and unexpected moves their dynamic has yielded along the way—like the oyster food truck the health department kiboshed, or the doughnut shop in Los Angeles that didn’t take. And show me a chef who seemed less likely to open a restaurant underneath the Amazon Spheres.

But the trio has an agreement: three yesses, or it’s a no. Their success seems to come from finding the path that each of these disparate personalities can live with. Forget the Space Needle, the coffee boom, the salmon tossing. This tension of craft versus commerce is Seattle’s essential story.

Image: Jonny Ruzzo

The partnership started with a note on a napkin. Or maybe it was a menu. In 2008, Chad Dale wanted to talk to Renee Erickson, the chef at Boat Street Cafe, about maybe opening a second restaurant in his redevelopment project in Ballard. He loved Erickson’s food, but had no way to contact her. So he showed up at Boat Street and left her a message.

“He did that more than once,” says Erickson. “And I was like, you’re crazy.”

Crazy persistent. Dale and some partners were redeveloping the Kolstrand Building, a handsome old Ballard Avenue structure that began life as a marine supply shop in 1910. It was his first commercial real estate project. And one of the last commercial projects approved before the financial meltdown. The bank, he says, was not happy and wanted to pull out. He was an unproven entity and needed a marquee tenant, stat, to harden the cement on the financing.

Erickson, meanwhile, was ready to think about something new. She’d bought Boat Street from founder Susan Kaplan. In the Kolstrand Building, she could create something from scratch. And the idea of a Northwest version of France’s casual oyster bars had been on her mind for years. Though she initially looked at the restaurant space, which would seat 200 people, and passed. Her vision called for something small.

Ultimately she and Ethan Stowell split the room between them; Erickson requested the back portion, a former loading dock with little aesthetic appeal and almost no street presence. If she was going to do this, she needed a trusted partner to run her little restaurant’s front of house while she was busy cooking.

Image: Amber Fouts

Price was a busboy at Boat Street at the time, doing calculus prereqs at community college to apply for a masters program in architecture. Instead, he found himself designing an oyster bar, and unknowingly shifting the trajectory of his career. Price built the shelves and banquettes with his father. Erickson supplied drawings from the artist, Jeffry Mitchell, and found a vintage chandelier at an antique shop in Los Angeles that reminded her of coral.

Less than a year after Walrus opened, the New York Times travel section ran a glowing story about Washington’s “wondrously watery” dining scene, complete with a photo of Walrus—and a majestic platter of oysters. The story printed on a Sunday; at dinner service that evening, the kitchen ran out of just about everything. Walrus’s brief tenure as a chill hidden-away oyster bar had come to an end. Only a handful of new restaurants get this kind of bounce, but Walrus has displayed a longevity that’s even more rare. Fourteen years later, diners still line up for seats a half hour before service begins.

“Walrus is one of those unicorn restaurants,” says Stowell, a chef whose own portfolio spans nearly 30 establishments from Edmonds to New York City. When we get on the phone, he walks me through a heart-palpitating account of just how fragile restaurants’ finances can be—and how quickly they can come undone without a constant eye to the big picture. He’s a chef who enjoys the balance sheets and P&Ls inherent to owning a restaurant group. “I feel like I have to know all that,” he says. “Whereas Renee has Chad and Jeremy.” Stowell was one of a handful of chefs Dale partnered with over the years. “His background is business and finance; he has the skill set to do it.” Besides, “Without the growth, Renee wouldn’t be able to do a couple cookbooks and be in Sicily.”

Dale originally signed on as a partner mostly because he could tell Erickson just wanted to focus on being a chef. The trio didn’t know one another well when they got in this boat together and started to row—Price and Dale didn’t know each other at all. The name Sea Creatures was still a few years off. But the small place they made together would vault them into some of the highest-profile spaces in the city.

Jeff Bezos never actually attended the many meetings that led up to Sea Creatures opening a bar and restaurant beneath the Amazon Spheres. But the company’s founder passed along plenty of notes and ideas. “There was so much effort in trying to make it his,” Erickson recalls. “He’s been there twice.” He even suggested a name, via his delegates: Happy Bottom Riding Club.

Bezos, of course, is a notable fan of aviation. The Happy Bottom Riding Club is a 1940s-era dude ranch run by a historic female aviator, Florence “Pancho” Barnes. It became a hangout for test pilots from the nearby military base, even shows up in Tom Wolfe’s book The Right Stuff. Still. Outside of that very specific context, Happy Bottom Riding Club suggests less aerodynamic activities. Especially for a bar tucked beneath a set of enormous balls.

Image: Amber Fouts

When Amazon started to turn the Denny Regrade area into a satellite of its South Lake Union corporate campus, it recruited local restaurants and businesses that bring texture to other Seattle neighborhoods. By then, Sea Creatures had opened the Whale Wins in another Chad Dale building project on Stone Way (these days it’s under different ownership). Erickson had won a James Beard Award in 2016. The chef known for oysters had also opened Bateau, a steak house that created a new paradigm around the environmentally harmful aspects of serving beef. For a time, Sea Creatures even raised its own cattle. For a chef ambivalent about growth, says Dale, Erickson “has, and continues to have, so many really good ideas that can’t be played out in a single place.”

Visits to Brittany and Normandy inspired Bar Melusine, the oyster spot next door to Bateau (today it’s Boat Bar). Sea Creatures’ General Porpoise doughnut shop serves a filled brioche homage to London’s St. John Bakery Arch. Each of their places definitely has its own look, but Price’s designs blend Erickson’s affinity for all things homey and French with his more midcentury, minimalist leanings: “When we meet in the middle it tends to be interesting and beautiful,” was Erickson’s observation when Bateau opened—an assessment that remains true these years later.

It wasn’t a surprise that Amazon wanted to talk. Or that Dale quickly grasped the many business upsides. It was intoxicating to think about what they could do with an Amazonian budget, says Price. “The things we see in New York that we can’t afford here. This is our chance.”

Collectively, he and Erickson say no far more often than yes. The trio gets a few proposals a month, says Price, most of which he and Erickson ignore. The smart ones go directly to Dale. “He’ll send us stuff and we’re like, ‘nope,’” says Erickson. Some opportunities make great sense financially, but she balks at the idea of a simple cut-and-paste of an existing restaurant. “We could have opened 50 restaurants on the Eastside by now.”

Those odds make the projects that do happen even more interesting. There’s no better example of the memorable results Sea Creatures’ inherent push-pull can produce than the bar and restaurant they eventually opened beneath Amazon’s Spheres. Willmott’s Ghost serves the rustic street pizza Erickson devoured when studying abroad in Rome as an undergrad. The interior feels like Italian modernism through the eyes of George Jetson, especially since it’s encased in a bubble of glass and geometric steel.

Meanwhile, the bar one Sphere over eventually became Deep Dive (one of Amazon’s leadership principles is “dive deep”). Erickson still grimaces when you ask about the name, but local artist and curator Curtis Steiner helped fill the room with endless curios. To hold a delicate coupe, or hefty cut-glass tumbler in your hand here is to leave the world of backpacks and badges and enter someplace surreal and hyper-Edwardian. It’s like drinking inside the world of Lemony Snicket.

“It’s kind of the antithesis of who we are,” Dale acknowledges of the Amazon projects. But Sea Creatures’ identity was expanding. And refracting. And it was about to face one hell of a company culture stress test.

Unseasonable February sunshine pours through the glass of Westward’s atrium; half the people gathered around the long table wear sunglasses, even though we’re indoors. But this meeting’s subject matter isn’t nearly so bright. As seaplanes take off from Lake Union in the distance, Westward’s general manager, Kira Brink, reads some pretty grim January sales numbers from her laptop.

Image: Courtesy Eric Tra/Westward

It’s not the food. Chef de cuisine Mike Stamey has a particular knack for pulling dishes from up and down the Pacific coast and making a menu full of raw oysters, pozole, spicy clam dip, and seafood towers feel cohesive. And besides, Brink’s spreadsheet reports he hit his budget percentages on the nose. It’s the annual reality of running the city’s dreamiest summertime restaurant in a city where our spiritual summer doesn’t start until early July.

Every month, more or less, Price and Erickson (and sometimes Dale) caravan around to each of the Sea Creatures restaurants and conduct these “period reviews” with the general manager and executive chef. If Erickson’s personal brand involves oyster picnics and sun-splashed cookbook research, the reality involves a significant amount of meetings about happy hour sales and the sorry state of the bathroom plumbing at Walrus and the Carpenter. These days, the company has a reserve fund to bridge Westward’s quieter months. Not to mention a leadership team: the company-wide beverage, operations, and sales and marketing directors gather around the table along with the partners to brainstorm and troubleshoot.

Next, Price reads an incident report regarding a diner whose treatment of a server one evening required the employee to step off the floor to regain composure. Reservation software indicated similar behavior at another Sea Creatures restaurant. Easy consensus: decline this customer’s future reservations and issue a courtesy notification. “I’m happy to write that,” says Price.

An hour earlier, at the Walrus and the Carpenter meeting, Erickson steered a brainstorm about specials away from chicken potpie and suggested either Puglia crab legs from Alaska or bouillabaisse. She’s no longer in a kitchen nightly, but the chefs in her company know her ethos. “Letting the ingredients shine is a big thing for her,” says Stamey. He, in turn, layers in as many bold flavors—namely pickles and hot sauce—as he thinks the Ericksonian philosophy can support.

Dale wasn’t at this particular Westward meeting, but he’s the reason Sea Creatures is in this spot at all. In July 2018, Skillet founder Josh Henderson ended one of the frothiest growth spasms in Seattle restaurant history by selling nearly all his restaurants to Sea Creatures. Dale, a business partner in both restaurant groups, was the common link in this surprising form of financial triage.

Price and Erickson, two people who take joy in creating their own places, required extreme convincing to acquire a portfolio that included a ramen shop and a burger chain. Suddenly, Erickson found herself at the top of a stack of nearly 20 establishments. Sea Creatures, for a time, had more reach than even Tom Douglas and Ethan Stowell, the two Seattle chefs who’d become synonymous with empire building.

"It turned out to be a really great thing," says Erickson, because it brought Gerlich aboard. But Westward was the thing that got her to yes. The oyster-focused restaurant on the curve of Lake Union shoreline felt like a place she and Price could make their own. After a substantial gutting and redesign, of course.

Outside that particular stretch of shoreline, the acquisition proved culturally uneasy, even after Sea Creatures applied its twin levers of food and design. Erickson quietly overhauled the food at Great State; it became the sort of burger chain that only uses tomatoes (incredibly good tomatoes) when they’re in season. Saint Helens restaurant in Laurelhurst became a bistro named for Erickson’s mom. The ramen spot turned into King Leroy, a bar clad in vintage beer signs and Showbox posters; it was definitely the only spot in the Sea Creatures canon serving housemade jalapeno poppers.

Image: Amber Fouts

Restaurants are big, slow-moving, unpredictable things. To build more than one of them means missteps are inevitable. “I don’t know that we had the passion for fast-food burgers that we needed to do it well,” Price acknowledges. The ownership dynamic that landed Sea Creatures in this arrangement also helped them devise an exit strategy. In 2023 they sold Great State, King Leroy, and the shuttered Bistro Shirlee to Great State’s longtime operations director, Nathan Yeager. A few partners (namely Dale and Gerlich) helped finance the sale, which meant they could choose a person who felt right to take over, rather than limit themselves to buyers who had access to funds. “We’re pretty good at letting each other figure it out,” says Erickson. She dislikes the cheesiness of saying they’re like family, “but you know—we definitely love each other.”

That’s probably why she said yes to Sea Creatures’ newest project, the first one where Price and Dale will be the primary drivers—though we will unfailingly refer to it as a Renee Erickson spot. Dale was the one who first toured the new RailSpur complex near the stadiums. And Price is a Mariners and Seahawks season ticketholder who needed little convincing to make over the former FX McRory’s, a sports bar that exudes 40 years of Seattle history.

Image: Jonny Ruzzo

They got Erickson to yes, in part with the allure of helping to fill Seattle’s oldest neighborhood with people and energy. In April, Sea Creatures announced plans for a European-style tank brewery and beer hall, plus a nestled-in bar that will sell pizza by the slice.

Erickson is unfailingly candid: “That was a hard no for me for a really long time,” mostly because she's way more into wine than beer. But now she’s sharing menu ideas and thinking about the tiny, more Ericksonian full-service restaurant also planned inside the larger space.

“Restaurateur” is a funny word. And not just to say or spell. It smacks of the impersonal—of some faceless Big Brother diminishing the ineffable pleasure of dining into a spreadsheet, then ensuring it shows a profit. The chef is the name we connect with. The cookbook we buy and the Instagram we follow. Renee Erickson the chef championed oyster farmers at Walrus and the Carpenter and made one hell of a pork chop at Boat Street Cafe. Renee Erickson the restaurateur has exposed countless diners to the charms of more sustainable seafood, like mackerel, and helped a lot of people understand a good steak doesn’t have to be a rib eye. When she decided to stop serving king salmon at her restaurants, as she did in 2018 in a show of support for our resident orcas, it became a news story.

Together, she and Dale and Price pull off the existential acrobatics of giving Seattle what it wants in restaurants: Great food that supports local farms, served by employees with health insurance and paid time off, plus an annual companywide field trip to Hama Hama’s oyster farm. Beautiful dining rooms that enrich neighborhoods. And a brand that motivates people to pay the menu prices that make this all possible. It’s not easy, but it’s heartening that someone is able to do all this—even in Seattle, with its high costs and myriad hurdles to profitability.

For all Erickson’s hesitation to take on new projects, “I don’t know that I would have kept doing restaurants if I just had one,” she says. Her solo days running Boat Street Cafe were isolating and physically grueling. Without the scope of Sea Creatures, “I would burn out much faster.”

She and Price prize Sea Creatures’ sense of place, which makes them reluctant to open anything outside Seattle city limits. And then there’s Dale. “I have my own desire to grow Walrus,” he says. “I imagine a handful of Walruses spread around the country.” The financial upside could be significant. “Is there a more Northwest restaurant than Walrus? I’d love to bring what we do here to these other markets.”

Though even he knows this notion is an uphill conversation. “He would open 10 Walruses if he could,” is Erickson’s good-natured retort when I ask her about this. But who knows. There’s always a path, of some sort, that could lead to yes.